Ramachandran & Ors. Vs. Vijayan & Ors.

[Civil Appeal No. 2161/2012]

Sanjay Karol, J.

1. The instant appeal, preferred by the original defendants, assails the judgment dated 27.08.2009 passed by the High Court of Kerala in A.S. No. 563 of 1999 whereby the appeal was dismissed and the preliminary decree passed by the Trial Court in O.S.631/1999 was affirmed.

MARUMAKKATHAYAM CUSTOMARY LAW – AN INTRODUCTION

2. The present appeal concerns the devolution of property by way of traditional Marumakkathayam law. Prior to delving into the legal niceties, an understanding of certain foundation concepts is necessary.

3. The Hindu community being a vast and diverse community is governed by different schools of personal laws. Apart from the dominant Mitakshara school of law, some communities among Hindus have their own system of personal law like the Marumakkathayam law, the Nambudiri law or the Aliyasantana law. In the issue at hand, parties are admittedly governed by the Marumakkathayam law. With respect to Marumakkathayam law, this Court has stated in Achuthan Nair v. Chinnamu Amma1:

“6. The said law [Marumakathayam law] governs a large section of people inhabiting the West-Coast of South India. “Marumakkathayam” literally means descent through sisters’ children. There is a fundamental difference between Hindu law and Marumakkathayam law in that, the former is founded on agnatic relationship while the latter is based on matriarchate. The relevant principles of Marumakkathayam law are well settled and, therefore, no citation is called for.”

4. Under this law, tharwad, thavazhi, karanavan are dominant concepts with respect to joint family. A tharwad is a Marumakkathayam joint family comprising of a female ancestor, her children, her daughter’s children, her daughter’s daughter’s children and all such other descendants, however remote, in the female line. By necessary exclusion, only the immediate male heir is part of the tharwad while his progeny are not. A person belongs to tharwad of his or her mother only.2

Membership of a tharwad is acquired by virtue of birth alone and on death, his interest devolves upon the other members of the tharwad. Members of a tharwad do not have a fixed interest but a fluctuating one, subject to change as per the number of members of the tharwad. Unlike coparcenary in Mitakshara law which extends to three generations succeeding the last male holder of the property, the Marumakkathayam system gives equal rights to all persons, however remote.

5. A tharwad is a larger body which holds within itself many branches. These branches are known as thavazhi which is a group of descendants in the female line of a female common ancestor. A thavazhi can own properties, separate and distinct from tharwad properties. In other words, a marumakkathayee woman alongwith her children and further descendants, how low-soever, in a female line constitute thavazhi. The concepts discussed above would be best explained by way of illustrations as under:

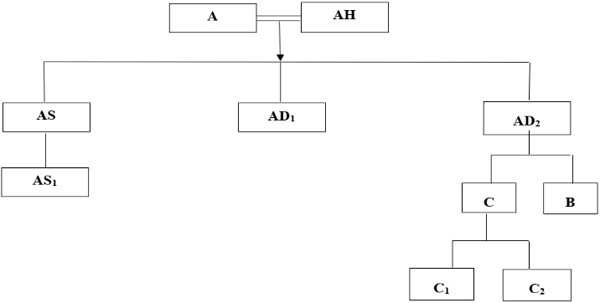

ILLUSTRATION:

A is married to AH. They have three children- two daughters, AD1 and AD2, and a son, AS. All members shown above with the exception of AS1 form the tharwad of A. This is in line with the matrilineal succession or in other words, the female being the ‘stock of descent’. AD2 with her children C, the daughter and B, the son and grandchildren C1 and C2 forms a thavazhi.

6. A karanavan is a manager of a joint family property. It is the oldest male member of the family. However, this customary position does not exclude a woman from managing the affairs of the tharwad or thavazhi if no male member is capable of taking up the required duties. Under Madras Marumakkattayam Act, 1932, it is defined as under:

“Section 3(c) ‘karanavan’ means the oldest male member of a tarwad or tavazhi, as the case may be, in whom the right to management of its properties vests or, in the absence of a male member, the oldest female member or where by custom or family usage the right to such management vests in the oldest female member, such female member;”

7. This Court explained the position of karanavan in Achuthan Nair v. Chinnamu Amma (supra)3:

“7. The management of a tarwad or tavazhi ordinarily vests in the eldest male member of the tarwad or tavazhi, as the case may be. But there are instances where the eldest female member of a tarwad or a tavazhi is the manager thereof. The male manager is called the karnavan and the female one, karnavati. A karnavati or karnavan is a representative of the tarwad or tavazhi and is the protector of the members thereof. He or she stands in a fiduciary relationship with the members thereof. But it is settled law that if a property is acquired in the name of the karnavan, there is a strong presumption that it is a tarwad property and that the presumption must hold good unless and until it is rebutted by acceptable evidence.”

(Emphasis supplied)

It is to be noted that, the position does not grant any special rights in the property and these rights standard part with any other member of the joint family.

BRIEF FACTS

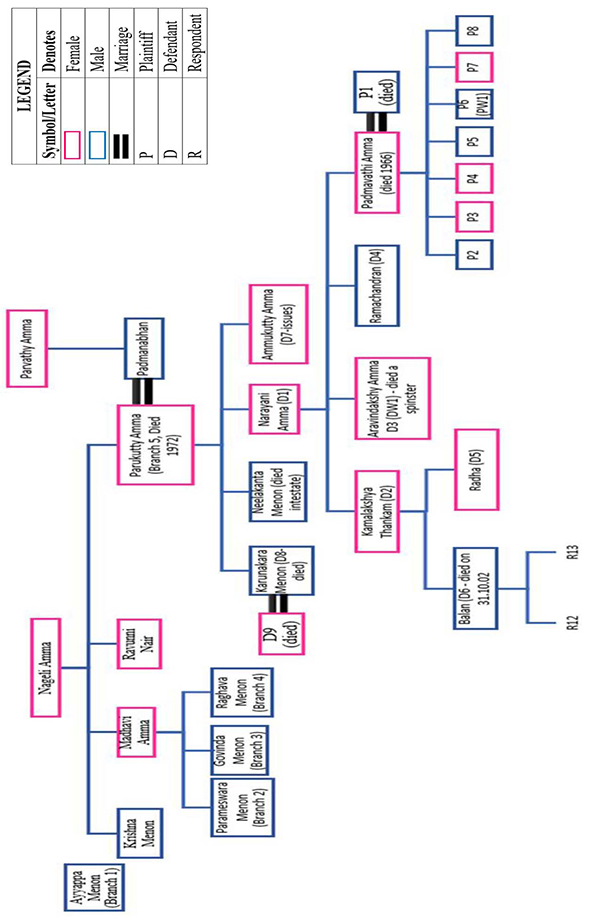

8. The facts which are necessary to dispose of the appeal are presented hereinbelow. For ease of understanding, a chart representing the genealogy is produced:

9. The dispute relates to the property of one Parukutty Amma. Parukutty Amma had four children namely Karunakara Menon, Neelakanta Menon, Narayani Amma and Amukutty Amma. Narayani Amma had four children namely, Kamalakshy, Aravindakshy Amma, Ramachandran and Padmavathi Amma. The husband and children of one of these four, Padmavathi Amma, are the plaintiffs. All other children and grandchildren of Parukutty Amma are the defendants except Padmavathy Amma. The defendants, having concurrently lost before all the courts below, are appellants herein. For ease of reference, the parties shall be referred, as per their position before the Trial Court.

10. A suit for partition and separate possession (O.S. No.631/1993) was filed by Plaintiffs no. 1-8 against Defendants before the Addl. Sub Court, Ernakulam4 for dividing the plaint scheduled properties belonging to Andipillil Tharwad by metes and bounds into 16 shares. Before us, the challenge pertains to two sets of scheduled properties- Item no.1 and Item no.2. Some preliminary understanding is required of how the properties subject matter of dispute came to be divided into two heads.

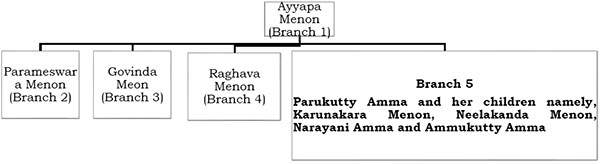

10.1 Item No.1: The property is situated in Ponnurunni Desom of Poonithura village and was part of the erstwhile Cochin state. It was gifted by one Krishna Menon in favour of 11 members of the same tharwad vide gift deed no.1223/1099. One of the donees, Ayyappa Menon filed a suit for partition5 of the said property against other donees. During the pendency of the suit, parties thereto entered into a compromise, and a partition deed giving effect to such compromise was executed dated 1.11.1950. The property was divided amongst nine donees as two, namely, Ravunni Nair and Madhavi Amma had passed away and it was mutually allotted to five branches as shown below:-

10.2 Item no.2: There was one Sankar Padmanabhan, on his demise, half of his property devolved on his wife, Parukutty Amma and their children; and another half on his mother, Parvathy Amma. His mother subsequently transferred her interest in the said property in favour of Parukutty Amma and her children through a mortgage deed.

TRIAL COURT

11. The Trial Court framed as many as eleven issues. Below is a tabulated representation of the eleven issues and their corresponding findings.

| Sr. No. | Issue | Finding | Decision |

| 1. | Whether the suit is time barred? | The plaintiffs can ignore the partition deeds since they are not binding on them, as execution of partition deeds by some of the members will not take away their right. | No |

| 2. | Whether the suit is bad for non-joinder of necessary parties? | The assignees of a partition of the plaint schedule properties were impleaded as additional defendants after the issues were framed. | No |

| 3. | Whether the plaint schedule first item property was the property of Andippillil Taravadu? | The executants of the partition deed formed a natural group of Marumakkathayees, that is, the matrilineal heirs, and this led to the conclusion that the property was tharwad property. | Decided in FAVOUR of the Plaintiffs. |

| 4. | Whether the Plaint Schedule second item property was the property of Andippillil Taravadu? | Property belonged to the thavazhi of Parvathy, as it was allotted to her and her son as per the recitals in the mortgage deed. The plaint schedule second item property thus belonged to the thavazhi of Parukutty Amma (through Parvathy’s son, Padmanabhan), as the property, obtained through a mortgage deed, was in the possession and enjoyment of the children of Parakutty Amma. | Decided in FAVOUR of the Plaintiffs. |

| 5. | Whether the alienations made by Neelakanta Menon are valid? | In Ammalu Amma and others v. Lakshmi Amma and other (1966 KLT 32) a Full Bench of the High Court held that the undivided interest of a member of a thavazhi cannot be alienated. So the alienations made by Neelakanta Menon are void. | No |

| 6. | Whether partition deed No.6143/1981 is binding on the plaintiffs? | Both items 1 and 2 were thavazhi properties the partition deed executed by 3 members alone does not bind the other members of the thavazhi. | No |

| 7. | Whether the alienations made by defendants 1 and 2 are binding on the plaintiffs? | The executants of partition deed did not have exclusive title to the properties and that document is not binding on the other members of the thavazhi. Hence, the subsequent transactions are also not binding on the other members. | No |

| 8. | Whether the alienation made by the 8th defendant is binding on the plaintiffs? | This transaction is also not binding on the other members of the thavazhi, as the property was a thavazhi property. | No |

| 9. | What is the share (if any) to which each of the co-owners is entitled in the plaint schedule properties? | Defendants 1 to 8 and plaintiffs 1 to7 are entitled to 1/15 shares. | 1/15 share |

| 10. | What is the amount (if any) to which defendants 13 and 15 to 17 are entitled as value of improvements? | . There is no evidence to show that they have made improvements to the properties thus, no relief can be granted to them even if there was any entitlement. | None |

| 11. | What is the order as to costs? | – | Costs to be borne out of the estate. |

12. It was concluded that the properties were tharwad property. A preliminary decree was passed allotting one share each to defendants 1-7 and plaintiffs 2-8 and one share to defendants 9-14 altogether. The relevant extract reads thus:

“In the result, a preliminary decree is passed in the following terms:-

1. The plaint schedule properties will be divided by metes and bounds into 15 shares.

2. Defendants 1 to 7 and plaintiffs 2 to 8 are entitled to one share each. Additional defendants 9 to 14 together are entitled to one share.

3. The plaintiffs will be put in possession of their joint 7/15 share.

4. The fifth defendant will be put in possession of her share.

5. The plaintiffs and fifth defendant are allowed to realize their share of income out of the shares of the other co-owners who will be liable proportionate to their shares.

6. The quantum of the share of income will be decided in the final decree proceedings

7. The costs shall come out of the estate”

13. For adjudication of the dispute before this Court, the findings returned in issues 3 and 4 are pertinent and the same are discussed in detail in the coming paragraphs.

14. In respect of item No.1, it was held that even though there was no evidence as to the original source of the property gifted by Krishna Menon, but the fact that the partition deed was executed by a natural group of Marumakkatayees led to the conclusion that the property was tharwad property. Parukutty Amma and her children forming part of a thavazhi and therefore being entitled to the property as members of the fifth branch is strengthened by the fact that the fifth branch comprising them was mentioned in the partition deed as a branch of Karunakaran Menon who was the Karnavan of the thavazhy. As such the conclusion drawn was that the property under item No. 1 was the thavazhi property of the fifth branch.

15. Issue no.4 before the Trial Court was in regard to item No.2. While answering in the affirmative, it was held that the said property would be tharwad property. Reasoning therefor was derived from the deed executed by Parvathy Amma in favour of Parukutty Amma and her children. The deed records that the former became the absolute owner of the property once Sankaran Padmanabhan died. Having become the absolute owner, she executed the said mortgage deed. Since Parvathy Amma was the absolute owner, she transferred the said property to her daughter-in-law and her successors.

HIGH COURT

16. The High Court, qua item No.1, has held that the share allotted to a female on partition retains the tharwad characteristic. It further held that since after the passing away of Madhavi Amma and Ravunni Nair, two of the eleven persons upon whom the property originally devolved, it was divided amongst nine surviving co-donees in 1950. It is clear that even at this point in time, the method adopted for succession was in line with the property being thavazhi in nature. It also relied on the testimony of DW-1 who deposed that Parukutty Amma and her children were separated as one thavazhi in the above-mentioned partition of 1950. 17. Qua item No.2, it was observed:

“The document is in favour of Parukutty Amma and her minor children. This mortgage was never redeemed by Parvathy Amma. Under the Prestine Marumakkathayam Law acquisition of a property in the name of mother and children who form a natural group had always been presumed to be on behalf of the tavazhi and even the existence of an original nucleus was not considered essential.

Since the acquirers under Ext.A2 mortgage namely Parukutty Amma and her minor children formed a natural group, the property would enure to all the members of the tavazhi of Parukutty Amma. It is pertinent in this connection to note that in Ext.B3 partition dated 28-10- 1981 as per which Karunakara Menon, Narayani Amma and Ammukutty Amma are alleged to have divided the property to the exclusion of the other tavazhi members including the plaintiffs, the title which is traced to plaint A schedule item No. 2 is ExtA2 mortgage and not ExtB 11 gift deed.

This also re-inforces the plaintiffs’ case that this item was acquired by Parukutty Aroma and her children as per ExtA2 mortgage.” and then concluded that since the acquirers under mortgage deed, namely, Parukutty Amma and her children formed a natural group the property would enure to all the members of the thavazhy of Parukutty Amma.

18. In terms of the above, the decree of the Trial Court stood confirmed by the High Court.

ARGUMENTS OF PARTIES

19. Learned Senior Counsel Mr. C.S. Vaidyanathan for the originaldefendants/ appellants submitted that the scheduled properties are not thavazhy property. It is submitted that item No.1 is a co-ownership property and item No.2 is a Putravakasam property. In so far as scheduled properties under item No.1 are concerned, the learned senior counsel submitted that the minority view expressed by the full Bench of the Kerala High Court in Mary Cheriyan & Anr. v. Bhargavi Pillai Bhasura Devi & Anr.6 should, in fact, be held as the correct view having regard to the difficulties of law noted by this Court in Achuthan Nair (supra).

20. For properties mentioned under item No.2, it is submitted that the property originally belonged to Kadangad Sankaran Padmanabhan and his mother could only execute gift deed as well as mortgage deed only to the extent of her own share and not the share of Padmanabhan.

21. Learned Counsel Mr. M.P. Vinod for the original plaintiffs/respondents submitted that a new tharwad is formed when a female member and all her children jointly receive properties by gift from another Marumakathayee. With respect to item No.1, it is submitted that when a share was allotted to the natural thavazhy vide partition deed dated 01.11.1950, then such natural thavazhy will also have the characteristics of a tharwad property. For item No.2, reliance is placed on partition deed 6143/1981 wherein it is specifically stated that Parvathy Amma became the sole owner after the death of her son thus she could validly transfer her share to Parukutty Amma and her children.

ISSUES

22. We have gone through the detailed pleadings of the parties. The bone of contention is the nature and character of the scheduled properties. After carefully going through the pleadings, the following two questions require adjudication :

1. Whether the property obtained by a female and her children after partition would be considered their separate property or would it belong to her tharwad?

2. Whether, in the present facts, Parvathy Amma had the legal right to transfer the entire property of her son to her daughter-in-law and grandchildren by way of a mortgage deed or was her right only limited to one-sixth of the property as contended by the original defendants?

APPRECIATION OF LAW

23. The case of plaintiffs is that scheduled properties being tharwad properties and they being members of the same are entitled to seek partition whereas defendants deny this claim.

Issue 1

24. This issue deals with the right of marumakkathayee female on partition. Partition is a process by which joint ownership is reduced to individual ownership. It puts an end to the joint status, separating members who hold their respective shares, which, on their death, will devolve upon their heirs. Under mitakshara law, if a member continues to be joint with his own male issue then the share allotted to him retains the characteristic of coparcenary property.

25. However, in Marumakkathayam law, as per the original defendants the position of law has been incorrectly settled.

26. The answer to the first question (supra), was answered, favouring the latter by the majority of the Full Bench of Kerala High Court in Mary Cheriyan (supra) but since the original-defendants are placing their reliance on minority opinion, we deem it necessary and appropriate to discuss all opinions expressed therein.

27. P.T. Raman Nayar, J., who penned the majority opinion, held that property obtained by a Nair female towards her share under an outright partition in her tharwad continues to retain its character as tharwad property. He propounded that on partition, a tharwad breaks up into separate units with each unit a tharwad by itself, called a thavazhi. Indubitably, the members added to a multi-member unit are entitled to the property obtained by tharwad partition the moment they become members thereof.

While placing the multi-member unit at par with a single-member unit, he observed that a single-member unit formed in a tharwad partition could add to its members by birth or adoption and thus become a joint family. Following this line of thought, he further opined that when a tharwad breaks up into units, the property allotted to a multi-member unit undisputedly shares the same character, so that members born into it thereafter get a right by birth. And as such, a similar right must be given to a single sharer (female) in the partition. The nature of tharwad property retains its character in the hands of the divided units after partition, thereby securing rights in the said property for persons yet to be born.

28. He further emphasized that, unlike Mitakshara law, which has a religious flair, Marumakkathayam law is read with a secular tone and thereby every member of a tharwad how low-so-ever in degree gets a right by birth, which extends even to the right by birth in property taken on partition.

Under the Marumakkattayam system, “a female is a stock of descent while the male is not”, which is why the children of a sole male sharer get no right to the property obtained by him on the partition, whereas a sole female sharer has to take it as tharwad property in which she must concede a share to her children, if she gives birth to any. Further, reliance was placed on Section 38 of the Madras Marumakkathayam Act before its amendment in 1958, which clarifies in its explanation that a sole sharer in a partition whether a male or a female, takes the share with the incidents of tharwad property.

29. However, the said opinion was not accepted by Govindan Nair, J., who observed that in Hindu Law, if ancestral joint family property is divided and a share taken by a father, a son born to that father after partition will only get an interest in that property by birth. The son takes such an interest by birth only because it is ancestral and not by reason of the fact that the property was joint family property or because it has retained its character as joint property. When an individual member obtains a share for themselves, the property ceases to be joint property after partition, thereby changing the nature of the property.

He differed with the interpretation of the majority opinion and by dissenting, opined that the statute enacted does not lay down or declare any general principle for the nature of property remaining a tharwad after the partition. The explanation to Section 38(2) of the Madras Marumakkattayam Act, 1932, before it was amended in 1958, only permitted a thavazhi partition and the absence of such an explanation in the Cochin Nayar Act, XXIX of 1113, which was enacted after the Madras Marumakkathayam Act further proves the intent of legislation to change the nature of property after the partition. He rejected the principle of “once a tarwad always a tarwad” as an outmoded concept.

30. Another minority opinion was expressed by Krishnamoorthy Iyer, J., who propounded that property obtained by a Nair female towards her share vide partition in her tharwad continues to be her separate property, notwithstanding the birth of a child to the female after the date of the partition. The result of partition is to convert, what was originally joint family non-ancestral property, into separate property. Further, reliance was placed on Mitakshara school of Hindu Law, which distinguishes the character of the property obtained by a co-parcener in the division of ancestral property and the shares received in the division of joint family property, not being ancestral property.

OUR VIEW

31. We have perused the judgments professing both the majority and minority views. The main point of disagreement between three learned judges on one side and two on the other, pertains to the question as to whether a female who, at the time of partition did not have any heirs, retains such property as her own or as tharwad property which she would have to eventually part with in favour of her children or descendants.

32. The majority, as is evident from the above, holds that a female who is single at the time of partition holds the property received in partition as tharwad by way of her being a single member thavazhi, thereby securing the right of persons who may become a member thereof either by way of adoption or birth in future. Per contra, the minority holds that if at the time of partition the female is single, she continues to hold the property as her own, even if she has children in the future.

This is for the reason that partition, by its very essence, alters the nature of the property from, at one point being jointly held property or tharwad to a property held solely by her. 33. Having given anxious consideration to both views, we conclude that the minority has, in fact, understood the position correctly. Partition is an act by which the nature of the property is changed, reflecting an alteration in ownership. At this juncture, we may take note of how the word partition is defined:

“- to divide into parts or shares

– to divide (a place, such as a country) into two or more territorial units having separate political status7

1. a division into parts; separation

2. something that separates, such as a large screen dividing a room in two

3. a part or share

4. a division of a country into two or more separate nations

5. property law a division of property, esp realty, among joint owners8.”

34. The Advanced Law Lexicon, Third Edition defines partition in the following terms:

“Partition is a division between co-owners (whether coparceners, joint-tenants in common) of lands, tenements and heriditaments held by them, the effect of such division being that the joint ownership is terminated, and the shares of the parties vested in them in severalty; [in mitakshara law, it] is the adjustment of diverse rights regarding the whole by distributing them on particular portions of the aggregate. Is a separation between joint owners or tenants in common of their respective interests in land, and setting apart such interest, so that they may enjoy and possess the same in severalty.”

The Hindu Succession Act, 1956 in the explanation to Section 6 provides that a partition is a partition in terms of this Law if it is made by way of a partition deed recognised under the Registration Act, 1908 or by a decree of Court.

35. It may be that a parcel of land for instance, may at one time, be owned by fourteen people but after partition is affected between them, with two people wanting no longer to be associated, the size of the land owned alongside the number of persons registered as owners both being reduced. What flows from this instance is that the two persons who separated from this collection of fourteen are now sole owners of their respective portions – the nature of the ownership being changed from joint to single.

36. In the present context, the difference of opinion referred to above hinges on who may constitute a membership of a thavazhi. The majority says a single person can be a thavazhi whereas the minority says not. The Madras Marumakkattayam Act, 1932 under Section 3(j)(i) defines thavazhi (in context of females) as a group of persons consisting of that female, her children and all her descendants in the female line.

37. Similarly, The Travancore Nayar Regulation, II of 1100 under Section 2(3) defines thavazhee of a female as a group of persons consisting of that female and her issue how-low-so-ever in the female line or such of that group as are alive. The same definition is employed in the Cochin Nayar Act, XXIX of 1113.

38. The common thread between the three definitions is that all of them refer to a group of persons, which includes the main female and her future generations. This necessarily implies that in order for a thavazhi to be formed, there has to be at least one female and her successive generation, either male or female, in the generation immediately succeeding and thereafter progeny of the female line.

39. The majority, here in our view, falters for in their understanding one single female is sufficient to form a thavazhi. For the reason above discussed and another which we shall come to in the following paragraphs, we are unable to agree with this view.

40. The second reason is the amendment to Section 38 of the Marumakkattayam Act, 1932 (Madras) carried out in 1958. The same is reproduced hereunder:

Prior to Amendment by Act 26 of 1958:

“38.(1) Any tavazhi represented by the majority of its major members may claim to take its share of all the properties of the tarwad over which it has power of disposal and separate from the tarwad:

Provided that no tavazhi shall claim to be divided from the tarwad during the lifetime of an ancestress common to such tavazhi and to any other tavazhi or tavazhis of the tarwad except with the consent of such ancestress, if she is a member of the tarwad. (2) The share obtained by the tavazhi shall be taken by it with the incidents of tarwad property.

Explanation – For the purpose of this Chapter, a male member of a tarwad or a female member thereof without any living child or descendant in the female line, shall be deemed to be a tavazhi if he or she has no living female ascendant who is a member of the tarwad.”

Post Amendment

“38. Right of member of tarwad or tavazhi to claim partition.- Any member of a tarwad or tavazhi may claim to take his or her share of all the properties of the tarwad or tavazhi over which the tarwad or tavazhi has power of disposal and separate from the tarwad or tavazhi.

Explanation 1.- Nothing in this section shall be a bar for two or more members belonging to the same tarwad or tavazhi claiming their shares of the properties and enjoying the same jointly with all the incidents of tarwad property.

Explanation 2.- The member or members who claim partition under this section or the member who claims or is compelled to take his or her sharae under section 39 shall be entitled to such share or shares of the tarwad or tavazhi properties as would fall to such member or members, if a division Per Capita were made among the members of the tarwad or tavazhi then living.

Explanation 3.- The provisions of the section shall apply to a tarwad notwithstanding the fact that immediately before the commencement of the Madras Marumakkattayam (Amendment) Act, 1958, the tarwad was included in the Schedule or that the tarwad had been registered as impartible.

Explanation 4.- The provisions of this section shall apply to all suits for partition, appeals and other proceedings arising therefrom filed or proceeded with by members or their legal representatives and pending in the Courts immediately before the commencement of the Madras Marumakkattayam (Amendment) Act, 1958, and such suits, appeals and other proceedings shall be disposed of in accordance with the provisions of this section as if this section were in force at the time of the institution of such suits, appeals and other proceedings.”

41. The majority placed its reliance on the pre-amendment version whereunder by virtue of sub-section (2) the position of law was that the share obtained by a thavazhi shall be taken by it with all incidents of it being a tharwad property. The abovementioned amendment removes the contents of sub-section (2) which demonstrates legislative intent to change the existing position of law.

That apart, per the discussion made above, a single person cannot form a thavazhi and, therefore, even the unamended section 38 cannot be read to be placing an obligation upon a single female inheriting property by way of partition, to hold it as tharwad property. We are in complete agreement with what Govindan Nair, J., observed in Para 56 of his dissenting judgment, which reads thus:

“56. The same rule cannot apply to the case of an individual member who obtain his share for himself. The property in such cases ceases to be joint property after partition. What really happens on partition is that the joint nature of the property is destroyed. I conceive that right by birth can be taken in property by a Marumakkathayee only if that property at the time of his birth was joint property.

The property allotted to a roup will be joint property and so children born in that group who normally take an interest in tarwad property acquire an interest in the property allotted to the group. But the same cannot be said when an individual member holds property, for such property has ceased to be joint property. On partition (forgetting for the moment those groups who take jointly) what happens is the destruction of the joint nature of the property. This happens even when there is only a division in status.”

42. Encapsulating the above discussion with reference to the illustration given earlier, it follows that neither the majority nor the dissenting Judges of the Full Bench have any qualms with the fact that upon partition AD2 would hold the property as tharwad property, thereby protecting the interest of C, B and other future generations. The disagreement stems when the devolution of property on partition upon AD1 is considered. The majority held that AD1 would become a single-member thavazhi and hold the property received by her as tharwad property protecting the interests of any children which, she may have in the future whereas the dissenting Judges held that since at the time of devolution AD1 did not have any children, she would acquire the property only in her own right.

43. Turning our attention back to the instant facts, it is not in dispute that Parukutty Amma and her descendants formed a thavazhi and had received the scheduled properties under item No.1 collectively. As we have already noticed above, the divergence of opinion between the minority and majority was in respect of single female(s) receiving property in partition.

That obviously is not the case here. All five Judges appear to be ad idem when it comes to property being received at partition by females and members of her thavazhi. Since the properties were received by the thavazhi and not by a woman who is single, the property is unquestionably tharwad property. Para 55 of the dissenting view expressed by Govindan Nair, J. captures as to how groups inherit property post-partition and how such property continues to hold tharwad characteristics. It runs as under:

“55. It is true that a tarwad need not always break up into its ultimate components; there may be branch divisions or some members may continue joint and continue to hold property and there may be several such groups and there can be a mixture of individuals holding property obtained on partition along with groups who hold jointly property allotted to each of those groups. The distinction to notice is that those groups hold property allotted to each group jointly.

No member of that group has any separate interest which he can claim as his own. His interests in the property allotted to the group is of an identical nature as the interests he had in the entire tarwad property before partition. In other words, the group holds the property with all the incidents of tarwad property as joint property. It is because property is so held as joint tarwad property that future tarwad members born in that group take an interest in the property allotted to that group.”

(Emphasis supplied)

44. Since there is no difference of opinion in this regard and further since the case before us is the inheritance of property by a group (branch 5), it falls in the second category (i.e. the category about which there is no dispute) no question arises as to determining the correctness of the view expressed, as is desired for us to do by the original-defendants.

45. Another aspect raised in connection with properties under item No.1 is that the property in question is held by co-owners and is not tharwad in nature. In our view, the High Court is correct in dismissing such an argument for, had it indeed been property co-owned, the heirs of the two deceased donees, Madhavi Amma and Ravunni Nair, would have also inherited their respective shares.

However, across all judicial fora the fact that the property devolved upon nine co-donees as opposed to eleven, as it was originally intended, has remained undisturbed. We find no reason to take a different view. Our conclusion that branch 5 held the property jointly is supported by the fact that the compromise deed, which granted them the said property, was never challenged before any Court of law. The parties consisting the 5th branch are:-

Parukutty Amma and her children, namely, 5-Karunaka Menon, 6-Neelakanda Menon, 7-Parukutty herself, 8-Narayani Amma and 9-Ammukutty Amma. This branch is known by the name of Karunakara Menon, who is one of the sons of Parukutty Amma as shown by the following words:

‘A scheduled item No.5 having value of Rs.750 and B schedule item no.3,4,5 debt is allotted to the share of 5th branch Karunakara Menon and others and the separate allocated share is taken possession by each branches.’

46. The appointment of Karunakara Menon as karnavan manifests the intention that the parties wished to jointly hold the property as tharwad. Karanavan, as eluded to earlier, is the manager of a joint family property similar in position to karta, however, not exactly the same. The person appointed to such a position is generally the eldest male member of the thavazhi.

47. In terms of the above conclusion, it appears that the original defendants’ reliance on the minority view may be misplaced as, at the cost of repletion, we may state that the difference of opinion was only with respect to inheritance by single females and not thavazhis.

Issue 2

48. Now adverting to the next issue, learned counsel for the petitioners make claim that the property under item No.2 is not governed by Marumakkathayam law but instead it is a puthravakasam property belonging to one Padmanabhan. The said fact is disputed by record as in a mortgage deed No.3181 executed by the mother of Padmnabhan, Parvathy Amma in favour of Purukutty Amma and her children, it is clearly stated that:

“The property described in the schedule is assigned in my favour as Pandaravaka puthuval pattom and I obtained pattayam and accordingly myself and son deceased Padmanabhan along with other branch members have executed partition deed and accordingly myself and the said Padmanabhan had obtained possession and after the death of Padmanabhan his every right over the property is inherited by me.”

(Emphasis supplied)

49. The above-extracted portion shows that Parvathy Amma, after the death of her son Padmanabhan, received the property in her own right. Apart from a few transactions, no other evidence was placed on record to prove that property was Putravakasha and not Marumakkathayam. Parvathy Amma executed the mortgage deed in favour of her daughter-in-law and her minor children. The possession was given to the mortgagee and it was never redeemed.

50. Learned Counsel for the petitioners also rely on partition deed No.6143/1981 executed by children of Padmanabhan and Parukutty Amma to hold that partition took place as putravaksham property but we find this argument misplaced. A relevant extract of the deed is reproduced below:

“Properties acquired in Survey 573 of Punnurunny Desom Poonithura Village by virtue of Document No. 1492/1950 of Thrippunithura SRO. (Book 1 Volume 600 Pages 389 onwards) and in Survey 691/2.690/1C of Vattekkunnam Kara Thrikkakara North Village by virtue of Document No. 3177/1096 of Alangad SRO. Were acquired by us along with our brother Late. Neelakandamenon alias Appu and mother Parukutty Amma and was in the joint possession and living together. After the death of our mother Parukutty Amma, all her rights are vested on us and the said properties are in the joint possession of us and we decided to partition.”

(Emphasis supplied)

51. A perusal of this deed shows that the said properties were acquired by them through different documents but nowhere it states that it devolved upon them after death of their father.

52. It is further pleaded that on the death of Padmanbhan, his wife and each of the children got an equal share by virtue of Section 22(1) of the Travancore Act as the said section deals with property acquired by gift or bequest from husband or father. No evidence is placed on record to show that the said property was gifted by Padmanbhan to his wife or children.

53. The Trial Court in regard to these properties (item No.2) held that:

“19. The second item property allegedly belonged to the tavazih of Parukutty Amma, the plaintiff’s predecessor, as per document No.3181/1096. The contention is that property belonged to Parukutty Am ma’s husband, Sankaran Padmanabhan of Kadangat taravadu, and not to Andippillil taravadu and the plaintiffs have no right over it. Padmanabhan and Parukutty Amma were the parents of deceased Neelakanda Menon and defendants 1,7 and 8. It is contended that Neelakanda Menon and defendants 1, 7 and 8 became entitled to the property as the legal heirs of their parents.

20. Ext. A2 Mortgage Deed is the document relied on by the plaintiffs. It is seen from the recitals in the document that the plaint schedule second item property was allotted to the share of Parvathy and her son Padmanabhan, husband of Parukutty Amma, in a partition and on the death of Padmanabhan Parvathy became its exclusive owner. It means that the property belonged to the tavazhy of Parvathy. It is mentioned in the document that Parukutty Amma of Andippillil tarvadu had been given possession of this item of property even before the execution of Ext. A2 mortgage deed Parukutty Amma was the great grandmother of the plaintiffs.

In 1116 M.E. Parukutty Amma’s son Neelakanda Menon executed a document in favour of his brother Karunakara Menon the 8th defendant in respect of this property. Ext. Bl is a copy of the registered deed. In the document it is mentioned that the property was obtained as per Ext. A2 mortgage deed and it was in the possession and enjoyment of the children of Parukutty Amma. So this document confirms that Neelakanda Menon and other claimed right over the property only under Ext. A2 mortgage deed. In 1981 the children of Parukutty Amma executed Ext. B3 partition deed dividing the plaint schedule 2nd item property amongst themselves.

The recitals in this document prove that they claimed right over the property only under Ext A2 mortgage deed (the -number of the document is wrongly shown as 3177). So the executants of Ext. B3 partition deed do not claim to have obtained right over the property independent of Ext. A2 mortgage deed. The contention of the defendants that the property belonged to Sankaran Padmanbhan is correct only to an extent; he had right only as a member of the marumakkathayam tavazhy of his mother.

When Sankaran Padmanabhan died his mother, Parvathy, became its absolute owner. She put it in the possession of Parukutty Amma and later executed Ext. A2 mortgage deed. The plaintiffs are descendants of Parukutty Amma in the female line. The evidence proves that the plaint schedule second item property also belonged to the tavazhy of Parukutty Amma.”

54. The observations of the High Court are already reflected in Para 16 of this judgment.

55. It is evident from the above that findings with respect to schedule properties in item No.2 are concurrent. This Court has reiterated many times9 that concurrent findings of fact are not to be generally interfered with unless special circumstances are shown warranting such interference. The scenarios in which exercise of power under Article 136 of the Constitution of India would be proper, non-exhaustively, can be culled out as thus:

55.1 Interference in concurrent findings has been termed justified if the finding –

a) recorded does not emanate from the pleadings;

b) is foreign to or entirely divorced from the evidence on record;

c) is reached on the basis of the evidence which is irrelevant or extraneous and material evidence is ignored affecting its sanctity;

d) runs contrary to any provision of law;

e) is such that a reasonable judicial mind could not have arrived at it and/or the same is arbitrary;

f) arrived at is perverse and the soundness of reason is compromised.

55.2 Apart from the above-mentioned scenarios, a Court would also be justified in interfering with findings concurrent in nature if it is of the view that they cause undue hardship to the parties.

55.3 Additionally, when the findings are such that the conscience of the court is shocked, interference would be called for.

56. While the above are some contexts in which the Court may exercise its plenary power, the following overarching principles should always be considered prior to delving into such exercise:

56.1 The power has to be used sparingly and only when grave injustice is being caused to the parties of the dispute;

56.2 The burden of proof to show that concurrent findings are unjust, warranting interference by this Court is on the appellant.

56.3 Interference would not be warranted merely because in a given set of facts, a view different from the one which stands taken by the courts below, is possible.

56.4 It is not within the realm of practicality that all possibilities be mapped out, as to when invocation of this power would be felicitous. The court has to take such a call having employed its wisdom, reason and judicial thought.

57. The above discussion on when interference in concurrent findings of fact will be justified demonstrates that while keeping in view the factors discussed in Para 51, any of the situations mentioned in Para 50 or other such similar situations, have to be met. In the present facts, we are of the considered view that none of the above scenarios appear to be so met. In that view of the matter, the findings of fact in respect of scheduled properties under item No.2 remain undisturbed.

58. The question of law, i.e., the difference of opinion between the majority and minority in Mary Cheriyan (supra) is resolved holding that the minority posited the correct view. However, it is clarified that the pronouncement of law in this judgment shall apply prospectively. For the purposes of ample clarity, we state that any transaction concluded or ongoing will not be disturbed by way of this judgment and the position of law as stated herein shall apply only henceforth.

59. In conclusion, even though we have, on the point of law upheld the minority view of the Full Bench of the Kerala High Court, in the facts of the present case, the finding about which all five judges were ad idem applies. The views of the Trial Court and the High Court therefore requires no interference by this Court.

60. Appeal stands dismissed. The preliminary decree passed by the Trial Court and upheld by the High Court is affirmed. The Trial Court to proceed further as per law.

61. No costs.

…………………J. (C.T. Ravikumar)

…………………J. (Sanjay Karol)

New Delhi;

November 22, 2024.

1 1965 SCC OnLine SC 303

2 K. Sreedhara Variar Marumakkathayam and Allied Systems of law in the Kerala State, First Edition, 1969

3 1965 SCCOnLine SC 303

4 hereinafter referred to as ‘Trial Court’

5 (O.S.77/1125)

6 1967 SCC OnLine Ker 68

7 https://www.merriam-webster.com

8 https://www.collinsdictionary.com

9 Srinivas Ram Kumar vs. Mahabir Prasad and Ors. 1951 SCC 136; Sree Sree Iswar Gopal Jieu Thakur v. Pratapmal Bagaria, AIR 1951 SCC 214; Addagada Raghavamma And Anr v. Addagada Chenchamma 1964 AIR SC 136; Variety Emporium v. V.R.M. Mohd. Ibrahim Naina, (1985) 1 SCC 251; Indira Kaur v. Sheo Lal Kapoor, (1988) 2 SCC 488; Mithilesh Kumari & Anr vs Prem Behari Khare (1989) 2 SCC 95; Sardar Jogendra Singh v. State of U.P., (2008) 17 SCC 133; Guljar Singh v. Dy. Director (Consolidation) (2009) 12 SCC 590; Ghisalal v. Dhapubai, (2011) 2 SCC 298; Sukhbiri Devi & ors v. Union of India & Ors. 2022 SCC OnLine SC 1322